An Industry Rushing Towards Massive Default?

November 13, 03

|

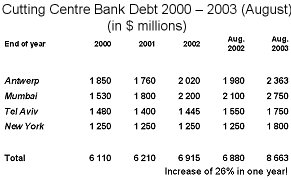

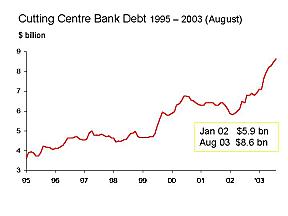

Though the formal banking indebtedness is $8.7 billion, the actual figure is much larger, as some of the huge (Indian) global players have converted banking debt into public debt through the issuance of bonds. Of course, all these figures can be explained – everything has a reason. But having “valid reasons” doesn’t mean that the indebtedness has a “reasonable chance” of ever being repaid. Both De Beers and bankers have stressed that companies are presently prepared to hold more inventory because interest rates are low. That is a very nice way of saying: companies are prepared to speculate that the inflationary value growth of inventories will exceed the cost of maintaining these inventories. One might call this perverse reasoning; it certainly shows that some people refuse to learn. Though rough prices have risen well in excess of 10%-13% in 2003 alone (and in some categories it is much more), the price of polished is still weakening. As long as the end-consumer only consumes polished (and not rough), it doesn’t make sense to finance excess rough inventories bought at overheated prices to begin with.

In our industry, were illusion and love are crucial images to be maintained at any price, we often avoid calling a spade – a spade. The skyrocketing debt is caused almost solely by two factors: (1) the shifting of inventories from the producers (mostly De Beers) to the manufacturers and (2) the need to invest (and thus finance) in both downstream marketing, brand development and jewelry ventures. When an Israeli or Belgian manufacturer acquires a jewelry chain in the United States or opens stores in Tokyo, the money has to come from somewhere.

So when we look at the almost $9 billion figure, we know that part of it represents money put in branding or marketing programs which have a high probability of never being successful. In other words: the money has gone. We also know that part of the money was used to finance grossly overpriced rough – that money is partly gone, unless polished prices will dramatically increase in the next few years. But this is a chicken and egg argument of “what comes first”. As long as the inventory overhang is so enormous (and in 2002 alone rough supply to the market was about $1 billion in excess of what was needed by the polished market), and the rough supplies exceed demand, polished prices have little chance to resume a healthy growth.

ABN-AMRO’s Peter Gross – the bank that is carrying over $2 billion of the overall industry indebtedness – has pointed out that the Indian industry, which is increasingly selling finished diamond jewelry products directly to U.S. retailers, has actually embraced a much larger financial risk as they finance the pipeline de-facto almost up to the consumer. What Gross didn’t stress is that the business models of the rough producers – and accepted by DTC sightholders and some others – will lead to a similar situation in other cutting centers. A greater part of the debt has a higher risk profile.

|

But neither the dramatically expanding risks of the borrowers, as identified by Peter Gross, nor the banks’ changes lending criteria as outlined by Paul Goris of ADB, can give comfort to the present $9 billion debt level.

In an uncertain future, there are a few trends which seem assured. First of all, the “industry shake-out” – i.e. the streamlining of Gareth Penny’s “spaghetti structure”, making many industry intermediaries redundant – will gain momentum in earnest in the immediate future. It is inevitable that there will be fewer players in our fragmented industry. Fewer players also mean less equity, less liquidity – and that’s bad news for the banks. Most soon-to-become-redundant players will gracefully disappear into oblivion; others will exit through bank default.

Another rather certain trend is the failure of some of the marketing programs which are now financed by banks. That doesn’t mean that the relevant borrower will default -- but it doesn’t help his financial situation either.

At the end of the day, the single most important contributor to a reversal of the rising debt trend is the market and its fundamentals. On the supply side, we do expect that rough supplies will increase at a greater pace in the near and immediate future than polished demand. That’s not good for the debt. We certainly expect the retail market to register a growth this year, and it may well grow more than the 2.5% of last year, but we are very conscious of discounting and of the fact that the unit prices of diamond jewelry pieces sold has been declining in recent years. Higher sales at lower margins translate into “mixed” news for the banks – which have already identified the low capitalization and unfavorable asset to debt ratios as one of the industry’s fundamental problems. This can only be rectified by bringing in “new money” (wishful thinking in most cases) or by creating profits – which is the ultimate aim of all players in this industry.

If it is fair to say that the diamond manufacturers turns around their capital, at best, twice a year (some do better; most do worse) – it is fair to say that, at $14.5 billion of annual polished consumption, the industry needs a working capital of $7 billion. As banks have made it a time-honored mantra to “finance working capital, not inventories” – it is clear that the banks are doing exactly what they don’t want to do: they finance inventories and uncertain downstream projects.

The weird thing is: the debt should have come down. The best thing that happened to the industry in the last few years is the tremendous increase in diamond manufacturing and marketing efficiency achieved by the industry in the past few years, unleashing or freeing considerable capital, increasing profit margins, which all should have contributed to a steep reduction of debt. Where is that money? That money has not been applied to the equity base of the manufacturer – but, rather sadly, to the margins of the rough producers, who increased prices – mostly to reduce their own debt, not because the market warranted the increases. In theory, when rough prices go up by two digits and polished continues to soften over an extended period of time, when there is an almost perennial lack of synchronization between rough and polished prices, the diamond manufacturers should go “bust”. They haven’t – so far.

What has “saved” them from more serious problems is, indeed, the greater manufacturing efficiencies in almost each and every operation. Some of the credit for this must certainly be given to the rough suppliers (mostly, but not only, DTC). The greater margins earned by the industry should have been applied to reduce the banking indebtedness.

The present unprecedented record level of banking debt should ring an alarm bell. Dismissing the growth by the observation that the low level of interest increases the willingness of the industry to carry stocks is giving the wrong message. Even a debt with a low interest rate is debt that needs to be repaid – and debts created to finance the purchasing overpriced rough are debts which will never be repaid. No market fundamental justifies the 40% increase in debt over the past 20 months. None whatsoever.